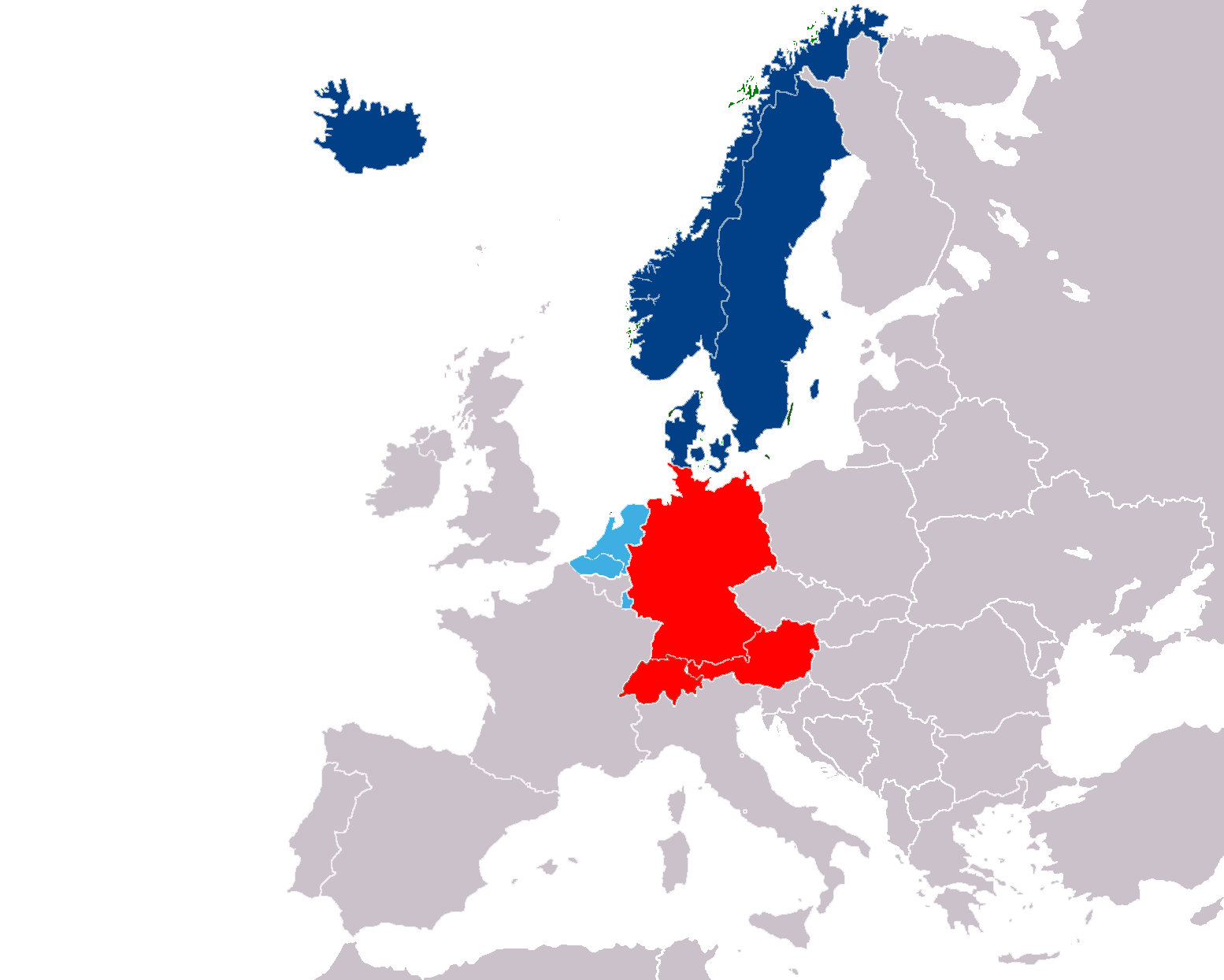

The 3×3 Concept: Building a Greater Germanic Union

The idea of a Greater Germanic Union can be understood through a simple yet powerful framework: three existing regional blocs, each consisting of three closely linked countries, brought together into a coherent nine-member structure. This “3×3” model is not only elegant in its design but also grounded in historical, cultural, and political realities that already exist.

The three building blocks

Benelux — The Low Countries

The Benelux (Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg) is the oldest formal regional union in Europe, predating even the European Union. It represents the historic unity of the Low Countries, with Flanders as the Germanic core of Belgium. Functionally, Benelux has strong legal and institutional structures, a common court, and a long tradition of economic and political integration.DACH — The German-speaking heart

Germany, Austria, and Switzerland are bound together by a common language family, shared cultural traditions, and dense economic ties. The DACH region is already a recognized concept in business, academia, and diplomacy, often treated as a single domestic market. Though less formalized than Benelux, it has enormous weight thanks to Germany’s economic size and Switzerland’s role as a financial and innovation hub.Nordic Cooperation — The Scandinavian core

Norway, Denmark, and Sweden form the heart of the Nordic Council. Their languages are mutually intelligible, their societies are deeply interconnected, and they share centuries of political, cultural, and economic cooperation. They pioneered free movement before Schengen existed, and continue to coordinate policy in areas like welfare, education, and sustainability.

Why the 3×3 framework is conceptually powerful

1. Rooted in existing institutions

Each bloc already has a recognized structure. Benelux has formal treaties and institutions; DACH is a well-established cooperation space in business and research; the Nordic Council is a durable political and cultural framework. This means that the Greater Germanic Union would not be invented from nothing — it would be an upward federation of existing regional building blocks.

2. Cultural and linguistic cohesion

Each triad is internally cohesive: the Low Countries share Dutch/Flemish linguistic roots; DACH is united by German as a lingua franca; the Nordics are linked by mutually intelligible Scandinavian languages. This makes each bloc easier to consolidate, and gives the union as a whole a cultural depth that can be mobilized without erasing diversity.

3. Geographic and strategic balance

The three blocs cover different parts of Europe’s Germanic space: maritime and lowland (Benelux), central and alpine (DACH), and northern and maritime (Nordics). Together they create a north–south spine and a west–east corridor, binding the North Sea, the Baltic, the Rhine and the Alps into one integrated geopolitical space.

4. Elegant symmetry and legitimacy

Nine members, grouped into three historically rooted blocs, offer a clear and symmetrical design that is easy to communicate politically and symbolically. This symmetry provides a sense of balance and fairness: no single bloc dominates, and each brings distinct strengths to the whole.

5. Functional complementarity

Benelux offers integration experience and logistics hubs (Rotterdam, Antwerp).

DACH offers industrial powerhouses and financial centers.

Nordics bring energy resources, welfare-state innovation, and green technology leadership.

Towards a Greater Germanic Union

The whole is more than the sum of its parts: a union that blends pragmatic governance, economic might, and social innovation. Taken together, these three mini-unions could form the foundation of a Greater Germanic Union of nine members, representing around 150 million people and generating a combined GDP of nearly US$9.4 trillion. More importantly, the union would rest on structures and identities that already exist and function, making it more realistic than a purely utopian project.

The 3×3 concept is therefore powerful not just as a symbolic model, but as a roadmap: strengthen each triad internally, then connect the triads together through a common council, and eventually move towards a federated framework. It is tidy, logical, and deeply anchored in European history — a modern vision with roots stretching back centuries.